The New York Taxi Ponzi Scheme

"The whole thing was like a Ponzi scheme because it totally depended on the value going up."

"The part that wasn't fair was the guy who's buying is an immigrant. They were conned."

Haywood Miller, debt specialist, New York

"People love to blame banks for things that happen because they're big bad banks."

"We didn't do anything, in my opinion, other than try to help small business people become successful."

Robert Familant, former head, Progressive Credit Union

"It was a safe and stable asset, and it provided a good life for those of us who were lucky enough to buy them [taxi medallions]."

"Not an easy life, but a good life. And then, everything changed."

Guy Roberts, in the Taxi industry since 1979

|

Symbolic coffins at a Wednesday protest by New York taxi drivers to mourn a series of recent suicides.

Mary Altaffer/AP

|

Years of driving for bosses he hated spurred Mohammed Hoque, 48, an immigrant from Bangladesh, to move up from driving taxis in New York City for others for the past nine years, to aspiring to acquire a medallion, the city permit that would legalize a yellow cab of his own. So when a businessman contacted him with an offer to sell a medallion, he bit. The offer was $50,000 would earn him the medallion, if he paid it immediately. For the rest, the businessman would help him obtain a loan.

Feverishly emptying his bank account, borrowing from friends, he rushed to the man's office to be handed a stack of papers in exchange for his cheque. Mr. Hoque signed, and left. That he had signed a contract requiring him to pay $1.7 million in total for the medallion escaped his notice. This is a man who had made about $30,000 for the year, 2014. Four years later, he had paid about $400,000 into the medallion fund, leaving $915,000 still owing, along with interest.

"It's an inhuman life. I drive and drive and drive. But I don't know what my destination is", he said, as he brought his third child home from hospital. Home, where his little family lived in the same cramped apartment; he had gained nothing, nothing at all. Who to fault? Well, Uber and Lyft come to mind. Pulling the taxi rug out from under drivers and fleet owners, right?

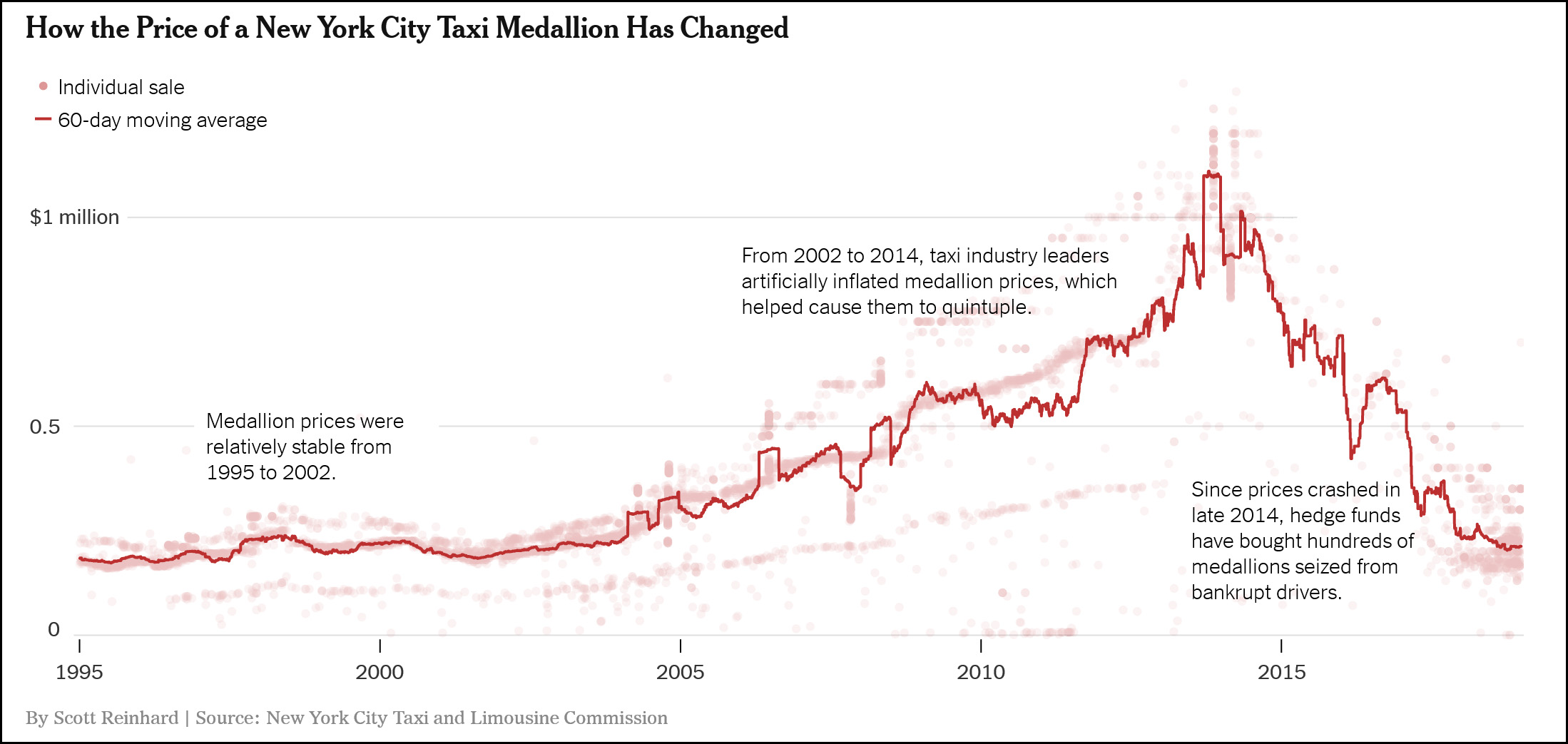

Evidently not. In the past year alone, eight suicides were noted, by New York City taxi drivers. An investigation by The New York Times appears to have uncovered an artificial price manipulation of taxi medallions; a bubble that would eventually burst. It took ten years, but it did. Thousands of drivers were channeled into reckless loans and hundreds of millions of dollars were extracted from them first, and then the market collapsed.

|

Drivers

assembled at City Hall on Wednesday afternoon called for "regulation

now," and demanded that the city "stop Uber's greed." Miranda Katz for Wired

|

Between 2002 and 2014 a medallion rose in price to over one million from $200,000, underwritten by banks and loosely regulated private lenders who wrote risky loans, encouraging refinancing, similar to what happened with the housing market crash that heralded the global economic meltdown of 2008. Driver incomes changed little, however.

It was the illusion and the trust that they owned something valuable that would enhance their earning potential that kept them in thrall to the system; hope over reason.

During that period, about four thousand drivers bought medallions, mostly of immigrant background. A Pakistani immigrant thought he was buying a car, ending up with a $780,000 medallion loan leaving him impoverished and unable to pay his rent, while a Bangladeshi immigrant was told to fabricate his income on his loan application and he eventually lost his medallion. When a Haitian immigrant worked exhaustively to hand over monthly payments he went bankrupt when he discovered he had been only paying interest.

Originally, taxi medallions were created by the city in 1937 to deal with the fact that unlicensed cabs crowded the city. City officials designated around 12,000 specialized tin plates, making it against the law to operate a taxi without one bolted on the car hood. Each medallion was sold for $10. They could be sold by those who bought them just as any other kind of asset would be. Soon an industry grew around he medallions where entrepreneurs bought up nonindependent medallions to build fleets, controlling the market.

Drivers working for fleets worked a typical 60 hours weekly, earning less than minimum wage, receiving no benefits. The legend thrived that driving could work as a pathway to join the middle class and where drivers could eventually buy an independent medallion to increase earnings and give them stability in an asset they could sell at some future date to fund their retirement years. At that time those who borrowed money for a medallion submitted a large down payment and had to repay within five to ten years.

Since the city released no new medallions for a half-century, values climbed steadily; $100,000 in 1984 and $200,000 by 1997. And then in the early 2000s a new cab industry generation took the reins; sons of longtime industry leaders who had new money-making ideas where the lenders accepted smaller down payments and eventually none at all, because interest on loans would provide all the incentive for the lenders and more, to essentially make money hand-over-fist.

"It got to a point where we didn't even check their income or credit score. It didn't matter", reminisced Monte Silberger, a former credit union official. As well, lenders encouraged borrowers to refinance when medallion prices rose, and as standards were relaxed even more, returns increased. Not through a rise in interest rates, but by enforcing a mix of extra costs; origination fees, legal fees, financing fees, refinancing fees.

Loan lengths were extended, with deals developed to last 50 years; some saw interest-only loans that could go on ad infinitum. Until 2014, when the bubble burst and medallion values fell, leaving borrowers to ask for breaks, but lenders called in their loans, deciding to leave the business. Some seized medallions and resold them profitably, others tried to get borrowers to surrender their homes.

As Mr. Hoqe said, it was an inhumane strategy for life.

Labels: Bankruptcy, Business, Corruption, Morals, New York City, Taxis

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home