Islamist Avoidance Illusions

"Anyone who achieves something in sports feels confident."

"He doesn't need to prove anything to anybody, and he won't try to achieve fame in a negative way."

"At this time in their lives [young men] are trying to prove something. They can find themselves in sports instead, and won't get involved in this stupidity."

Arsen Saitiev, school principal, Makhachkala, capital, Dagestan

"The coaches try to educate the athletes in all ways, not only in wrestling."

"They teach them how to behave in life [as well as on the wrestling mat]."

Abdul Kazanbiev, wrestler-in-training

"We always wrestled."

"The followers of the Prophet also wrestled, and as we are Muslims, wrestling came to us with Islam."

Adam Batirov, Bahrain team competitor, Makhachkala

|

| Yuri Kozyrev / NOOR for TIME The wrestlers of Chechnya and Dagestan compete as Russians |

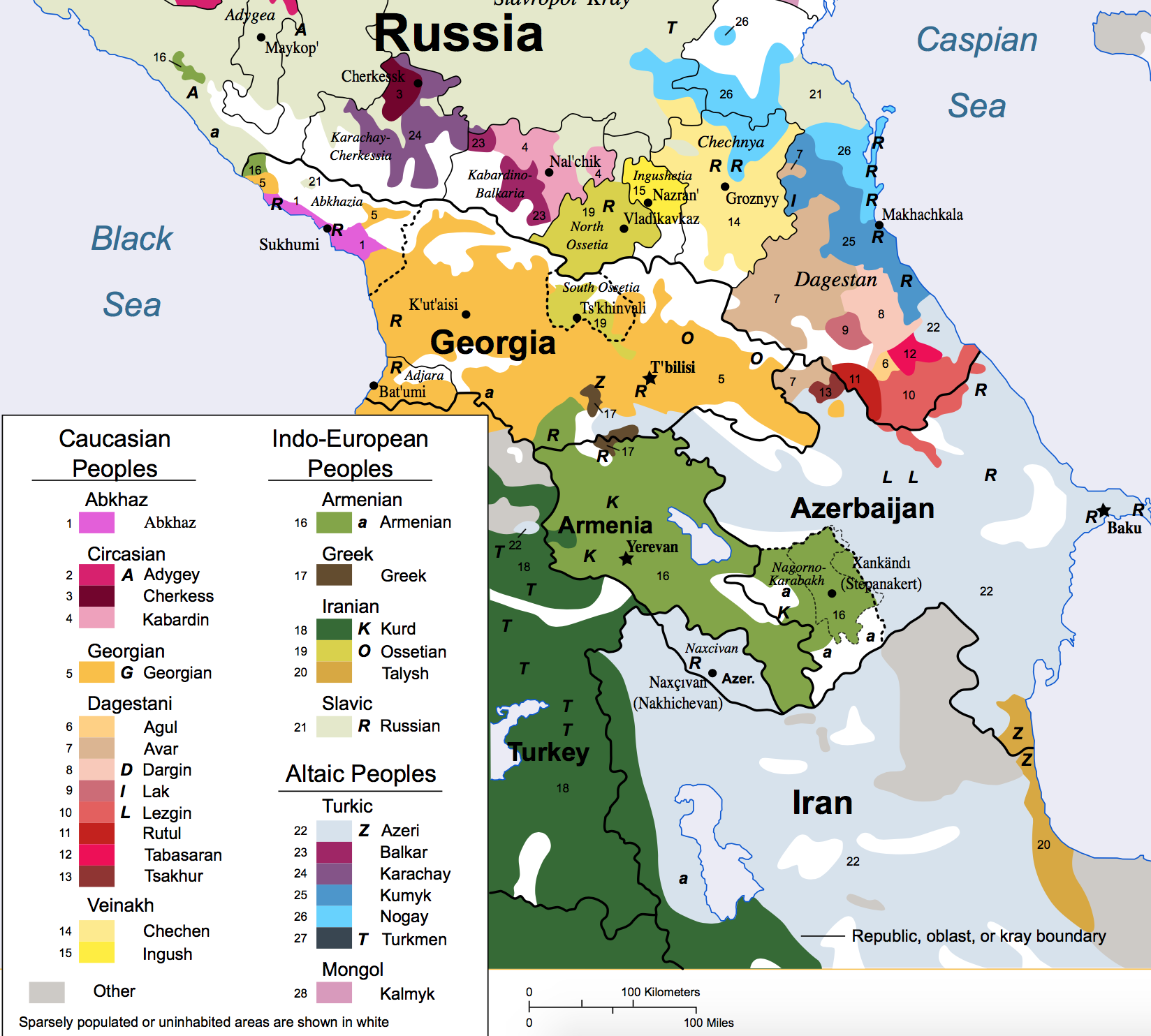

In the south of Russia lies Dagestan, a Muslim region on the coast of the Caspian Sea. It has a magnificent geology of mountainous landscapes where disparate regional ethnic groups live with a long heritage of wrestling as the national 'sport'. When those wrestlers from Dagestan (and Chechnya) appear as contestants at international elite sport events where they invariably dominate with their superior wrestling skills and training, they are celebrated as "Russian" athletes.

These are also areas in the Russian Federation where a long-established, violent Islamist insurgency continues to rage. Young boys are inducted early into the skills-training and competitive atmosphere, of wrestling, eager to distinguish themselves, emulating the successes of those they wholly admire who have proven themselves on the world stage as champions of the art of wrestling, winning medals at the Olympics.

They too dream of dominating the sport like Buvaisar Saitiev who won no fewer than three gold medals, or Maviet Batirov who won two, to further burnish the distinguishing wrestling prowess of Dagestan's muscled and lithe wrestling champions. Towns and villages view the sport and their youth involvement as central to their pride and honour, pouring resources into furthering the sport with gyms and top-flight coaches.

|

| Martial arts Booming in Dagestan RT |

In wrestling bouts between mountain villages, challenges between wrestlers have been traditional. Now, the entire region has fully involved itself in persuading as many of its youth to engage in wrestling as can be convinced, in a culture where wrestling already holds a pedestal position of singular achievement. There is an added incentive, however, one with a degree of urgency surrounding it; that steering boys and young men to the mat will steer them away from jihad.

It has become commonplace to see boys and young men run each morning along the Caspian Sea beaches, a traditional method of weight control and cardiovascular fitness intended to allow a wrestler to fall within the required weight category. On weekends, it's mountain trails the wrestlers take to, occasionally stopping to briefly spar. Wrestling equipment is not costly, a leg up in poor communities; one-piece suit or singlet and shoes.

Coaches and athletes pray together in the wrestling gyms, attributing a religious significance to the sport. Certainly aiding in visualizing wrestling positively through the lens of Islam. Hundreds of men have left the region to join Islamic State in Syria. And attacks against Christian churches in the region by ISIL recruits occur on occasion. Russia is forever on the alert to pick up intelligence about the potential presence of Islamist insurgency.

So the broader Dagestan community's focus on turning their men from radical Islam to wrestling is understandable. And does it work? There is this example reported from Chechnya by Time magazine several years back:

In a nasty signal of how intransigent this conflict has become, wrestling has started to produce rebel fighters in Khasavyurt, and the idea that this sport could serve as an antidote to Islamism has foundered. On the night of April 18, near a bridge overlooking a Soviet-era cinder-block factory, three men were killed in a firefight with Khasavyurt police. Two of them were later identified as professional wrestlers, including Ramazan Saritov, 28, who almost made the cut for Russia’s Olympic team in 2004 and 2008. According to Russian security forces, he was the leader of a group of insurgents who were wanted for car bombings, ambushes against police and attacks on stores that sell alcohol. Five days after the shoot-out, local Islamists posted a “martyr video” online to mourn Saritov’s death. In one of the frames, he wears a T-shirt with the words russia wrestling team as he points a semi-automatic pistol in the air.

Ibragim Irbaykhanov, director of the wrestling school where Saritov and the Saytiev brothers began their careers, remembers Saritov as a clever fighter on a generous athletic stipend who had just built a house in Khasavyurt for his young family. “He could have gone to the Olympics [in London] in the 60-kg division,” Irbaykhanov says. “I have no idea what he was thinking.” But this was not an isolated incident. In 2008 the 15-year-old wrestling champion Movsar Shaipov was killed in a shoot-out with police just outside Khasavyurt. Two years later, the same thing happened to another local fighter, 19-year-old Nariman Satiev, a three-time world champion in Thai boxing. “There are so many that it’s complicated,” Adam says. “Some are forced into it. Others get fed up with the security forces. They get arrested once, twice, and soon it’s easier for them to go somewhere and start shooting back.”

|

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home